A (Nearly) Branchless RESP Request Parser

Posted: 2025/09/15 Filed under: code Comments Off on A (Nearly) Branchless RESP Request ParserI’ve been messing around with Garnet at work a lot lately – a Redis compatible, highly scalable, mostly C# remote cache. This brought an old idea back to mind, and I decided to actually hash it out this time – can you write a branchless RESP request parser, and would it be worth it?

Framing The Problem

Defining some terms up front:

- RESP – the REdis Serialization Protocol, a human readable protocol for communication with Redis and related (Valkey, DragonflyDB, the aforementioned Garnet) databases/caches. Tends to look like

+OK\r\n or $5\r\nhello\r\nor*1\r\n$5\r\nworld\r\n. - RESP Request – A RESP array of at least 1 item, where every element is a bulk (ie. length prefixed) string, and the first element is a (case insensitive) command name. Looks so “get the value under ‘fizz’” looks like

*2\r\n$3\r\nGET\r\n$4\r\nfizz\r\n. Nearly all operations against a Redis compatible server will be RESP requests. - Branchless code – Code which, once compiled/JIT’d/etc., has no branching assembly instructions like JMP, JGE, CALL, etc.. For C# the “once JIT’d” is an important distinction, as the intermediate code generated by the compiler may or may not have branches but I only care about what ultimately executes.

- Nearly branchless code – A term I’m inventing right here, to mean code that has a small number of necessarily highly predictable branches. Sometimes it’s just “worth it” to have a branch because the purely branchless code is so much worse – typically this is in cases where there’s some edge case that needs handling for completeness, but which happens rarely-bordering-on-never in practice.

What’s “worth it?” – While this is inherently a judgement call, I will compare my approach to a naive RESP request parser and one based on Garnet’s (which is decidedly not naive) on metrics of code size, performance, and maintainability. Spoiler – it’s probably not.

The interface I’ll implement is as follows:

public static void Parse( |

Command and scratch buffer sizes are determined by the implementation, not the caller, and created with helpers. We take the two sizes in mostly for integrity checking in DEBUG builds, but they do have some real uses.

The Parse(…) method takes the input buffer and parses ALL of the RESP requests in the filled portion. I do this because when using Redis (or similar) if you aren’t pipelining then, IMO, you don’t care about performance. It follows that in a real world workload the receive buffer will have multiple commands in it.

Incomplete commands terminate parsing, as does completely filling the output span. A malformed command results in a sentinel being written to the output after any valid commands that preceded it, and parsing terminates. Incomplete commands are typically encountered because some buffer in transmission (on either client or server) filled up, which isn’t guaranteed to ever happen but is hardly uncommon.

When Parse(…) returns,commandsSlotsUsed indicates how many slots were filled, which will cover all complete commands and optionally one malformed sentinel. Likewise bytesConsumed indicates all bytes from fully parsed and valid commands.

Insights and Tricks

Before diving into the implementation, there are a few key insights I exploited:

- The minimum valid RESP request is 4-bytes:

*0\r\n- This is arguably invalid since all requests should have a command, but using 4 lets us reject sooner

- Although RESP has many sigils, for requests only digits are of variable length

- Accordingly, we know exactly when all other sigils (in this case,

*,$, and\r\n) are expected - The maximum length of any valid digits sequence is 10, just large enough to hold 2^31-1

- If we have a bitmap that represents which bytes are digits, we can figure out how long that run of digits is with some shifting, a bitwise invert, and a trailing zero count

- The possible commands for a RESP request are known in advance, so a custom hashing function can be used as part of validation – though care must be taken not to accept unexpected values

- We can treat running out of data the same as encountering some other error, except we don’t want to include a sentinel indicating malformed in the output

ParsedRespCommandOrArgumentis laid out so that allbyteStart == byteEnd == 0represents malformed,command > 0represents the start of a command request, and anything else represents an argument in a request- If our “in error” state is an int of all 0s (for false) or all 1s (for true), we prevent or rollback changes with clever bitwise ands and ors

The Branches

The code is dense and full of terrors, so although I will go over it block by block below I doubt I can make it easy to follow. To emphasize the cheats that make this “nearly” branchless, I’m listing the explicit branches and their justifications here:

- When we build a bitmap of digits, there’s a loop that terminates once we’ve passed over the whole set of read bytes

- Because we require the command buffer to be a multiple of 64-bytes in size, the contents of this loop can be processed entirely with SIMD ops. It still needs to conditionally terminate because the buffer size is determined at runtime, and it is difficult-bordering-on-impossible to guarantee the buffer will always be full.

- There’s a loop that terminates if we hit its end with the “in error” state mask set, this is used to terminate parsing when we either encounter the end of the available data or a malformed request is encountered

- The number of requests in each buffer read is expected to be relatively predictable given a workload, but highly variable between workloads. This means we basically HAVE to rely on the branch predictor.

- However, it is expected that almost all request buffers will be full of complete, valid, requests, so we don’t exit the loop early ever – we only have the final check of the

do {... } while (...).

- When parsing numbers, we have a fast SWAR path for values <= 9,999 and a slower SIMD path for all larger numbers.

- In almost all cases, lengths are expected to be less than 9,999 so this branch should be highly selective. We must still handle larger numbers for correctness.

- When parsing the length of an array, we have an even faster fast path for lengths <= 9 and then fallback to the number parsing code above (which itself has a fast and slow path).

- RESP workloads tend to be dominated by single key get/set workloads, which all fit in fewer than 9 arguments (counting the command as an argument).

- Accordingly, this branch should be highly selective.

This amounts to 5 branches total, not counting the call into the Parse(...) function or the return out of it. The JIT (especially with PGO) will introduce some back edges, but we will expect a factor of ~2x there.

The Code

I’ve elided some asserts and comments, full code is on GitHub.

Build The Bitmap

var zeros = Vector512.Create(ZERO); |

First, I build the aforementioned bitmap where all [0-9] characters get 1-bits. This loop exploits the over-allocation of the command buffer to only work in 64-byte chunks (using .NET’s Vector512<T> to abstract over the actual vector instruction set).

Then, after some basic setup, we enter the per-command loop. This is broken into 4 steps: initial error checking, parsing the array size, extracting each string, and then parsing the command.

Per-Command Loop

const int MinimumCommandSize = 1 + 1 + 2; |

The initial error check updates our state flags if we have insufficient data to proceed, insufficient space to store a result, or a missing * (the sigil for RESP arrays). These patterns for turning conditionals into all 1s occur throughout the rest of the code, so get used to seeing them.

var arrayLengthProbe = Unsafe.As<byte, uint>(ref currentCommandRef); |

Then we proceed into parsing the actual array length. We use one of our branches on special casing very short arrays (<= 9), then handle reasonably sized arrays (<= 9,999), and then finally handle quite large arrays (10,000+).

One subtlety here is that RESP forbids leading zeros in lengths, something many parsers get wrong. Accordingly we have to do some range checks in all paths except the fastest path – both slower paths use a lookup to determine if the final result is lower than the lowest legal value for the extracted length.

At the end of parsing the array length, we have some number of items to parse AND might have set inErrorState or ranOutOfData to all 1s.

// first string will be a command, so we can do a smarter length check MOST of the time |

Next we optimistically try to read a string with length < 10. This will almost always succeed, since the expected string will be a command name AND most RESP commands are short. There’s no fallback for longer strings, because we’ll handle those in a more general loop that follows.

Note that the bounds of the parsed string are written into the results, but only if inErrorState is all 0s – otherwise we leave the values unmodified through bit twiddling trickery. Also observe that we actually update the ParsedRespCommandOrArgument fields as longs instead of the individual ints they’ve been decomposed into, as a small efficiency hack.

// Loop for handling remaining strings |

The loop which follows handles the remaining strings in a command array. This strongly resembles the above except instead of just having a path for strings of length < 10 it has two paths, one for strings of length <= 9,999 and one for everything else.

Peppered throughout that code are places where we track old values (like oldInErrorState) or enough data to reverse a computation (like rollbackWriteIntoRefCount). These are then applied conditionally, but without a branch, where needed – again using bit twiddling hackery.

// we've now parsed everything EXCEPT the command enum |

Then we have what is probably the trickiest part of the code, parsing the first string in a command array as a RespCommand. This uses a custom hash function, conceptually, derived through a brute force search.

The idea is to:

- Load the command text into a SIMD register

- Mask away bits to force the command to be upper case

- Perform a simple hash function (in this case an XOR, a dot product, and a mod by a constant factor)

- Lookup the expected RespCommand and command string given that hash

- Compare the command string to what we actually have, erroring if there’s no match

One subtlety is that RESP commands sometimes have non-alpha characters. For the set I handle here, a comparison against ‘z’ is sufficient to exclude collisions that the basic approach can’t.

This hash approach could probably be greatly improved upon. The function is very basic, and there’s a vast literature on fast (or perfect) hash functions to draw upon.

// we need to update the first entry, to either have command and argument values, |

After parsing the command, we end the main loop with some error handling and update the first ParsedRespCommandOrArgument to its final (either malformed or command w/ arguments) state.

Wrapping Up

// At the end of everything, calculate the amount of intoCommandsSpan and commandBufferTotalSpan consumed |

Finally, after exiting the main loop, we calculate how many bytes we consumed and ParsedRespCommandOrArgument slots we used. Recall that, if we entered an error state, we rolled back advances to currentIntoRef and currentCommandRef – so we’ll be left pointing at the start of the incomplete or malformed command.

The Assembly

To prove the assertion about branches in the final code, here’s the JIT’d assembly. This is x86 assembly, generated in .NET 8 on an AMD Ryzen 7 machine with PGO and tiered compilation enabled.

; Assembly listing for method OptimizationExercise.SIMDRespParsing.RespParserFinal:Parse(int,System.Span`1[ubyte],int,int,System.Span`1[ubyte],System.Span`1[OptimizationExercise.SIMDRespParsing.ParsedRespCommandOrArgument],byref,byref) (Tier1) |

For a total of 11 branches. The JIT has introduced 6 of these, mostly 5 backedges as a consequence of getting the likely-to-run-code close together (which trades branches for fewer reads from memory and reduced instruction cache pressure). One oddball is the jmp G_M000_IG08, which appears replaceable to me – perhaps there’s an alignment concern, or a branch distance issue I’m not seeing.

That’s inline with my desires so far as codegen goes. The likely hot path has the five explicit branches, and the worst case path doubles it.

The Performance

With any benchmarking, we first have to define what we’re comparing to. In this case, I’m comparing to:

- A naive RESP parsing implementation I threw together

- One based on Garnet with a couple tweaks

- It correctly rejects leading 0s

- I’ve removed sub-command parsing

- I’ve contorted it to produce

ParsedRespCommandOrArgumentinstead ofSessionParseState

My top level benchmark varies the mix of commands, the size of the batches, the size of various sub elements, and what percentage of batches are incomplete. The full set of results can be found here, but here are some of the highlights.

This SIMD/nearly-branchless approach is a bit smaller than Garnet, though the Naive approach (which makes many more function calls) is smaller than both:

| Method | Code size (bytes) |

| Naive | 2,016 |

| Garnet | 5,189 |

| SIMD | 3,610 |

We see that as the command mix increases, SIMD does increasingly well but the Garnet approach remains superior. This is probably because Garnet doesn’t treat all commands equally, special casing common commands with faster parsing. Since I chose common commands to benchmark, Garnet does quite well. As the mix of commands includes more that aren’t special cased, the branchless and SIMD approach closes the gap.

Both SIMD and Garnet deal well with larger batch sizes, and much better with randomly varying sizes.

Batches being incomplete doesn’t show an inflection point, suggesting that the reduction in data to parse dominates any misprediction penalty in the Garnet or SIMD cases.

So across the board in what I consider the interesting cases, the SIMD/nearly-branchless approach is close to, but a little worse, than the Garnet approach – excepting code size. Given the trends, I would expect that the SIMD approach is best when the mix of commands aren’t specially cased by Garnet, and batch sizes are large.

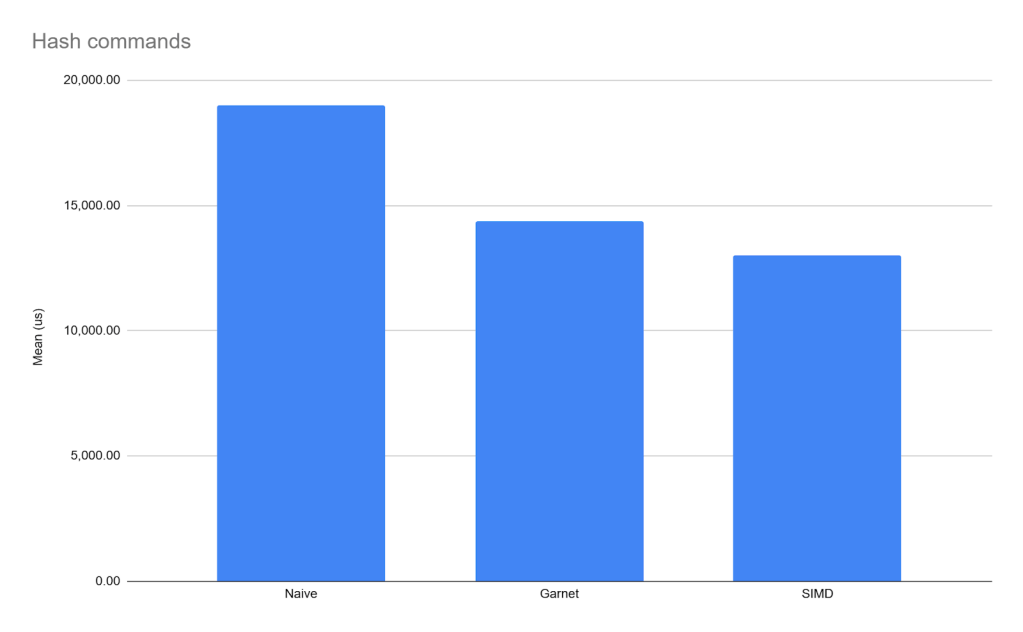

And that is what we see with the “just hash commands”-case, since Garnet doesn’t special case HDEL, HMGET, or HMSET. As an example:

Is It Worth It?

While an interesting exercise, on the balance no.

The fundamental issue is, if your workload falls predictably into Garnet’s assumptions (which are reasonable) the performance just isn’t there – the SIMD/nearly-branchless approach isn’t faster.

Beyond that, this code is also disgustingly un-maintainable.

But there are some things that might shift the balance:

- A pointer-y implementation might be a bit more maintainable

- I did this all with refs since that would allow un-pinned memory for the command buffers, but realistically you’re gonna be reading from a socket and if you really care about perf you’ll pull that memory from the pinned object heap

- More optimizations around command parsing are possible

- Commands are parsed twice, once to find boundaries and then once to determine the RespCommand – these could be combined

- The hash calculation isn’t very sophisticated, a better implementation may be possible as mentioned above

- Garnet’s big-ol’ switch approach for parsing gets a little worse for each implemented command, and Redis has a lot of commands

- In fact, the implementation I used here has removed a lot of commands in comparison to mainline Garnet

- I’ve used .NET’s generic VectorXXX implementation, specializing for a processor (and its vector width) might yield gains

- While this wouldn’t introduce branches at runtime, it would make the code even harder to maintain

- Instruction cache and branch prediction slots are global resources, so the smaller and nearly branchless approach frees up more of those resources for other work

- Any benefit here would be workload dependent, as these resources are allocated dynamically at runtime

Of course, some of the nearly-branchless approaches (like the hashing command lookup) could be adopted independently – so a hybrid approach may come out ahead even if the balance shifted.

While always a little disappointing when an exercise doesn’t pan out, this sure was a fun one to hack together.