A (Nearly) Branchless RESP Request Parser

Posted: 2025/09/15 Filed under: code Comments Off on A (Nearly) Branchless RESP Request ParserI’ve been messing around with Garnet at work a lot lately – a Redis compatible, highly scalable, mostly C# remote cache. This brought an old idea back to mind, and I decided to actually hash it out this time – can you write a branchless RESP request parser, and would it be worth it?

Framing The Problem

Defining some terms up front:

- RESP – the REdis Serialization Protocol, a human readable protocol for communication with Redis and related (Valkey, DragonflyDB, the aforementioned Garnet) databases/caches. Tends to look like

+OK\r\n or $5\r\nhello\r\nor*1\r\n$5\r\nworld\r\n. - RESP Request – A RESP array of at least 1 item, where every element is a bulk (ie. length prefixed) string, and the first element is a (case insensitive) command name. Looks so “get the value under ‘fizz’” looks like

*2\r\n$3\r\nGET\r\n$4\r\nfizz\r\n. Nearly all operations against a Redis compatible server will be RESP requests. - Branchless code – Code which, once compiled/JIT’d/etc., has no branching assembly instructions like JMP, JGE, CALL, etc.. For C# the “once JIT’d” is an important distinction, as the intermediate code generated by the compiler may or may not have branches but I only care about what ultimately executes.

- Nearly branchless code – A term I’m inventing right here, to mean code that has a small number of necessarily highly predictable branches. Sometimes it’s just “worth it” to have a branch because the purely branchless code is so much worse – typically this is in cases where there’s some edge case that needs handling for completeness, but which happens rarely-bordering-on-never in practice.

What’s “worth it?” – While this is inherently a judgement call, I will compare my approach to a naive RESP request parser and one based on Garnet’s (which is decidedly not naive) on metrics of code size, performance, and maintainability. Spoiler – it’s probably not.

The interface I’ll implement is as follows:

public static void Parse( |

Command and scratch buffer sizes are determined by the implementation, not the caller, and created with helpers. We take the two sizes in mostly for integrity checking in DEBUG builds, but they do have some real uses.

The Parse(…) method takes the input buffer and parses ALL of the RESP requests in the filled portion. I do this because when using Redis (or similar) if you aren’t pipelining then, IMO, you don’t care about performance. It follows that in a real world workload the receive buffer will have multiple commands in it.

Incomplete commands terminate parsing, as does completely filling the output span. A malformed command results in a sentinel being written to the output after any valid commands that preceded it, and parsing terminates. Incomplete commands are typically encountered because some buffer in transmission (on either client or server) filled up, which isn’t guaranteed to ever happen but is hardly uncommon.

When Parse(…) returns,commandsSlotsUsed indicates how many slots were filled, which will cover all complete commands and optionally one malformed sentinel. Likewise bytesConsumed indicates all bytes from fully parsed and valid commands.

Insights and Tricks

Before diving into the implementation, there are a few key insights I exploited:

- The minimum valid RESP request is 4-bytes:

*0\r\n- This is arguably invalid since all requests should have a command, but using 4 lets us reject sooner

- Although RESP has many sigils, for requests only digits are of variable length

- Accordingly, we know exactly when all other sigils (in this case,

*,$, and\r\n) are expected - The maximum length of any valid digits sequence is 10, just large enough to hold 2^31-1

- If we have a bitmap that represents which bytes are digits, we can figure out how long that run of digits is with some shifting, a bitwise invert, and a trailing zero count

- The possible commands for a RESP request are known in advance, so a custom hashing function can be used as part of validation – though care must be taken not to accept unexpected values

- We can treat running out of data the same as encountering some other error, except we don’t want to include a sentinel indicating malformed in the output

ParsedRespCommandOrArgumentis laid out so that allbyteStart == byteEnd == 0represents malformed,command > 0represents the start of a command request, and anything else represents an argument in a request- If our “in error” state is an int of all 0s (for false) or all 1s (for true), we prevent or rollback changes with clever bitwise ands and ors

The Branches

The code is dense and full of terrors, so although I will go over it block by block below I doubt I can make it easy to follow. To emphasize the cheats that make this “nearly” branchless, I’m listing the explicit branches and their justifications here:

- When we build a bitmap of digits, there’s a loop that terminates once we’ve passed over the whole set of read bytes

- Because we require the command buffer to be a multiple of 64-bytes in size, the contents of this loop can be processed entirely with SIMD ops. It still needs to conditionally terminate because the buffer size is determined at runtime, and it is difficult-bordering-on-impossible to guarantee the buffer will always be full.

- There’s a loop that terminates if we hit its end with the “in error” state mask set, this is used to terminate parsing when we either encounter the end of the available data or a malformed request is encountered

- The number of requests in each buffer read is expected to be relatively predictable given a workload, but highly variable between workloads. This means we basically HAVE to rely on the branch predictor.

- However, it is expected that almost all request buffers will be full of complete, valid, requests, so we don’t exit the loop early ever – we only have the final check of the

do {... } while (...).

- When parsing numbers, we have a fast SWAR path for values <= 9,999 and a slower SIMD path for all larger numbers.

- In almost all cases, lengths are expected to be less than 9,999 so this branch should be highly selective. We must still handle larger numbers for correctness.

- When parsing the length of an array, we have an even faster fast path for lengths <= 9 and then fallback to the number parsing code above (which itself has a fast and slow path).

- RESP workloads tend to be dominated by single key get/set workloads, which all fit in fewer than 9 arguments (counting the command as an argument).

- Accordingly, this branch should be highly selective.

This amounts to 5 branches total, not counting the call into the Parse(...) function or the return out of it. The JIT (especially with PGO) will introduce some back edges, but we will expect a factor of ~2x there.

The Code

I’ve elided some asserts and comments, full code is on GitHub.

Build The Bitmap

var zeros = Vector512.Create(ZERO); |

First, I build the aforementioned bitmap where all [0-9] characters get 1-bits. This loop exploits the over-allocation of the command buffer to only work in 64-byte chunks (using .NET’s Vector512<T> to abstract over the actual vector instruction set).

Then, after some basic setup, we enter the per-command loop. This is broken into 4 steps: initial error checking, parsing the array size, extracting each string, and then parsing the command.

Per-Command Loop

const int MinimumCommandSize = 1 + 1 + 2; |

The initial error check updates our state flags if we have insufficient data to proceed, insufficient space to store a result, or a missing * (the sigil for RESP arrays). These patterns for turning conditionals into all 1s occur throughout the rest of the code, so get used to seeing them.

var arrayLengthProbe = Unsafe.As<byte, uint>(ref currentCommandRef); |

Then we proceed into parsing the actual array length. We use one of our branches on special casing very short arrays (<= 9), then handle reasonably sized arrays (<= 9,999), and then finally handle quite large arrays (10,000+).

One subtlety here is that RESP forbids leading zeros in lengths, something many parsers get wrong. Accordingly we have to do some range checks in all paths except the fastest path – both slower paths use a lookup to determine if the final result is lower than the lowest legal value for the extracted length.

At the end of parsing the array length, we have some number of items to parse AND might have set inErrorState or ranOutOfData to all 1s.

// first string will be a command, so we can do a smarter length check MOST of the time |

Next we optimistically try to read a string with length < 10. This will almost always succeed, since the expected string will be a command name AND most RESP commands are short. There’s no fallback for longer strings, because we’ll handle those in a more general loop that follows.

Note that the bounds of the parsed string are written into the results, but only if inErrorState is all 0s – otherwise we leave the values unmodified through bit twiddling trickery. Also observe that we actually update the ParsedRespCommandOrArgument fields as longs instead of the individual ints they’ve been decomposed into, as a small efficiency hack.

// Loop for handling remaining strings |

The loop which follows handles the remaining strings in a command array. This strongly resembles the above except instead of just having a path for strings of length < 10 it has two paths, one for strings of length <= 9,999 and one for everything else.

Peppered throughout that code are places where we track old values (like oldInErrorState) or enough data to reverse a computation (like rollbackWriteIntoRefCount). These are then applied conditionally, but without a branch, where needed – again using bit twiddling hackery.

// we've now parsed everything EXCEPT the command enum |

Then we have what is probably the trickiest part of the code, parsing the first string in a command array as a RespCommand. This uses a custom hash function, conceptually, derived through a brute force search.

The idea is to:

- Load the command text into a SIMD register

- Mask away bits to force the command to be upper case

- Perform a simple hash function (in this case an XOR, a dot product, and a mod by a constant factor)

- Lookup the expected RespCommand and command string given that hash

- Compare the command string to what we actually have, erroring if there’s no match

One subtlety is that RESP commands sometimes have non-alpha characters. For the set I handle here, a comparison against ‘z’ is sufficient to exclude collisions that the basic approach can’t.

This hash approach could probably be greatly improved upon. The function is very basic, and there’s a vast literature on fast (or perfect) hash functions to draw upon.

// we need to update the first entry, to either have command and argument values, |

After parsing the command, we end the main loop with some error handling and update the first ParsedRespCommandOrArgument to its final (either malformed or command w/ arguments) state.

Wrapping Up

// At the end of everything, calculate the amount of intoCommandsSpan and commandBufferTotalSpan consumed |

Finally, after exiting the main loop, we calculate how many bytes we consumed and ParsedRespCommandOrArgument slots we used. Recall that, if we entered an error state, we rolled back advances to currentIntoRef and currentCommandRef – so we’ll be left pointing at the start of the incomplete or malformed command.

The Assembly

To prove the assertion about branches in the final code, here’s the JIT’d assembly. This is x86 assembly, generated in .NET 8 on an AMD Ryzen 7 machine with PGO and tiered compilation enabled.

; Assembly listing for method OptimizationExercise.SIMDRespParsing.RespParserFinal:Parse(int,System.Span`1[ubyte],int,int,System.Span`1[ubyte],System.Span`1[OptimizationExercise.SIMDRespParsing.ParsedRespCommandOrArgument],byref,byref) (Tier1) |

For a total of 11 branches. The JIT has introduced 6 of these, mostly 5 backedges as a consequence of getting the likely-to-run-code close together (which trades branches for fewer reads from memory and reduced instruction cache pressure). One oddball is the jmp G_M000_IG08, which appears replaceable to me – perhaps there’s an alignment concern, or a branch distance issue I’m not seeing.

That’s inline with my desires so far as codegen goes. The likely hot path has the five explicit branches, and the worst case path doubles it.

The Performance

With any benchmarking, we first have to define what we’re comparing to. In this case, I’m comparing to:

- A naive RESP parsing implementation I threw together

- One based on Garnet with a couple tweaks

- It correctly rejects leading 0s

- I’ve removed sub-command parsing

- I’ve contorted it to produce

ParsedRespCommandOrArgumentinstead ofSessionParseState

My top level benchmark varies the mix of commands, the size of the batches, the size of various sub elements, and what percentage of batches are incomplete. The full set of results can be found here, but here are some of the highlights.

This SIMD/nearly-branchless approach is a bit smaller than Garnet, though the Naive approach (which makes many more function calls) is smaller than both:

| Method | Code size (bytes) |

| Naive | 2,016 |

| Garnet | 5,189 |

| SIMD | 3,610 |

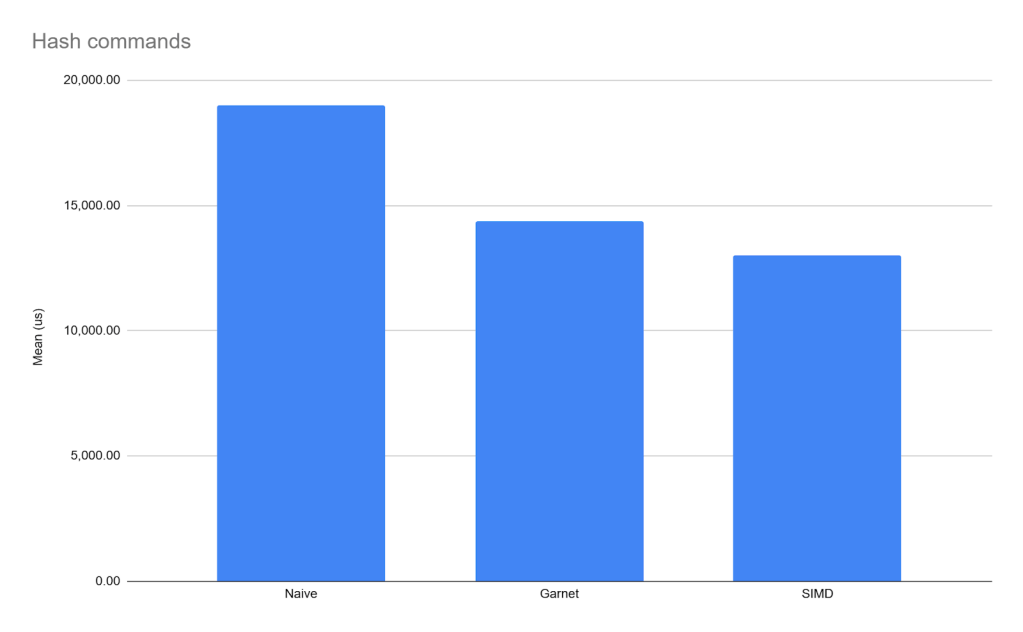

We see that as the command mix increases, SIMD does increasingly well but the Garnet approach remains superior. This is probably because Garnet doesn’t treat all commands equally, special casing common commands with faster parsing. Since I chose common commands to benchmark, Garnet does quite well. As the mix of commands includes more that aren’t special cased, the branchless and SIMD approach closes the gap.

Both SIMD and Garnet deal well with larger batch sizes, and much better with randomly varying sizes.

Batches being incomplete doesn’t show an inflection point, suggesting that the reduction in data to parse dominates any misprediction penalty in the Garnet or SIMD cases.

So across the board in what I consider the interesting cases, the SIMD/nearly-branchless approach is close to, but a little worse, than the Garnet approach – excepting code size. Given the trends, I would expect that the SIMD approach is best when the mix of commands aren’t specially cased by Garnet, and batch sizes are large.

And that is what we see with the “just hash commands”-case, since Garnet doesn’t special case HDEL, HMGET, or HMSET. As an example:

Is It Worth It?

While an interesting exercise, on the balance no.

The fundamental issue is, if your workload falls predictably into Garnet’s assumptions (which are reasonable) the performance just isn’t there – the SIMD/nearly-branchless approach isn’t faster.

Beyond that, this code is also disgustingly un-maintainable.

But there are some things that might shift the balance:

- A pointer-y implementation might be a bit more maintainable

- I did this all with refs since that would allow un-pinned memory for the command buffers, but realistically you’re gonna be reading from a socket and if you really care about perf you’ll pull that memory from the pinned object heap

- More optimizations around command parsing are possible

- Commands are parsed twice, once to find boundaries and then once to determine the RespCommand – these could be combined

- The hash calculation isn’t very sophisticated, a better implementation may be possible as mentioned above

- Garnet’s big-ol’ switch approach for parsing gets a little worse for each implemented command, and Redis has a lot of commands

- In fact, the implementation I used here has removed a lot of commands in comparison to mainline Garnet

- I’ve used .NET’s generic VectorXXX implementation, specializing for a processor (and its vector width) might yield gains

- While this wouldn’t introduce branches at runtime, it would make the code even harder to maintain

- Instruction cache and branch prediction slots are global resources, so the smaller and nearly branchless approach frees up more of those resources for other work

- Any benefit here would be workload dependent, as these resources are allocated dynamically at runtime

Of course, some of the nearly-branchless approaches (like the hashing command lookup) could be adopted independently – so a hybrid approach may come out ahead even if the balance shifted.

While always a little disappointing when an exercise doesn’t pan out, this sure was a fun one to hack together.

Thoughts On Truth In Our Time

Posted: 2025/01/16 Filed under: code, pontification | Tags: ai, technology, truth 3 CommentsAnybody else been thinking about the truth recently? Not “why doesn’t everyone agree with me, the obviously correct person” – but how do people learn something, decide it is true, and how do falsehoods become truths to so many?

Anyone? Anyone? Bueller?

Obviously the 2024 election, shall we say, heightened my concerns but I’ve been mulling this over for a year or so. A couple anec-datum really stood out to me when talking with folks over that time.

One was being told that NYC had banned gas stoves in a blatantly unconstitutional move, which I kinda doubted, in part because I live in NYC and have a gas stove. Best I can tell, this is a garbling of a 2023 NYS budget requirement that buildings built starting in 2026 don’t have gas hookups (though there are numerous exceptions). The median NYC building is something like 90 years old, so calling this a ban is just not true in either a de jure or de facto sense. And yet, there are loads of Google hits for “NYC gas stove ban” asserting it is.

Another was hearing that raising tariffs on Chinese goods would lower grocery prices. This is not how tariffs work, definitionally they impose a tax which raises prices. I’m sure lots of you saw that Google Trends search making the rounds, which suggests this confusion isn’t isolated. Plus the US doesn’t import much food (some light Googling suggests ~15%), and even that’s mostly from Canada and Mexico (which makes sense, since food is often bulky and perishable).

Both of these were in person, group gatherings, with people I had existing relationships with – not randos on the internet. And I want to emphasize, I’m not concerned about whether these are good policies (I have mixed opinions of both) but about the truth-ness of these assertions and how the people making them came to believe them.

Truth Is Expensive, Lies Are Cheap

It is tempting to blame malicious actors, and I think there is something to that, but at scale I think a lot of the problem is economic.

It took me about an hour to write the preceding 3(-ish) paragraphs, most of it spent digging up citations (for things I was already familiar with), not counting the vague musings I’ve had over the past year. It would take about 90 seconds to read it out loud. A typical news segment is 2 minutes long, a Youtube video averages 10 minutes, a podcast averages maybe 40 minutes. Optimistically that’s a 40x ratio of “time spent researching” to “content”.

It’s much cheaper to just make something up. Or copy from someone else, who is also incentivized to make something up.

One of the takeaways from Hbomberguy’s (very long) plagiarism video is how plagiarism is a natural consequence of the drive for ever increasing amounts of “content.” I believe the ease with which falsehoods spread has clear parallels.

While not new to our times (“Lie Can Travel Halfway Around the World While the Truth Is Putting On Its Shoes” is a quote [erroneously] attributed to Mark Twain in the early 1900s), the volume and “democratization” of it is. Some random Jungian psychologist can start a Youtube channel and become shockingly influential, if you paid attention to US politics you probably encountered a feline feces themed Twitter user at least once, if you’re a programmer you’ve probably read a lot of some random ex-Microsofty’s blog and know it’s influence. You’re reading a random current-Microsofty’s blog right now. I wouldn’t say any of this is new but it is different.

Authority And Consensus

There’s a question I’ve pointedly left unanswered thus far – what makes something true?

This is such a tricky question there’s a whole branch of philosophy about it, epistemology, which is interesting in its own right. Unfortunately, at least as a layperson surveying the field, it doesn’t appear to have many concrete applications. Perhaps a reader will point me at a useful concretization?

For my purposes I assert that, in the real world, what people consider to be true is perceived consensus amongst recognized authorities. I believe this definition can be justified, and provides some useful insights.

In terms of justification, for one I think it matches how we behave in reality. If you feel sick you go to a doctor who diagnoses you. You trust the doctor’s opinion because some authority has certified them as a doctor, and their training (established by a consensus of other doctors) informs the diagnosis. At no point are you, the patient, truly capable of evaluating their work but (at least in general) you will accept their conclusions as true.

This definition also explains my experiences in the introduction. Why did my family/friends/colleagues believe these falsehoods? Because they heard them on the news, or from a candidate from a major political party, or from a trusted person. That a claim was broadcast implies it had some verification behind it (even it didn’t), a mention in a candidate’s speech implies the party as a whole supports it (even if they don’t), and a person you trust is assumed to be applying the same standards recursively (even if, sometimes, they’re just thinking out loud).

It also explains things that aren’t (generally) believed. There are plenty of people who’ll tell you evolution is fake, or the Earth is only a few thousand years old, or aliens built the pyramids, or Taylor Swift’s dating habits are to sway election results. For most claims, it is impractical for the listener to refute or verify them, but because these people are not perceived as authorities their claims are not considered true. We all watched the Higgs boson’s existence become true as authorities (who I am not fit to judge) came to a consensus (that I am not fit to contribute to) that it had been detected. We still don’t know the whole “truth” of dark matter (its existence, its composition, how much, do we need it, do we need it, do we need it) despite many authorities expressing opinions, because there is no consensus amongst them.

A useful insight is that truth is built up iteratively – it’s not that something “is” true, it’s that many people come to an agreement that it is. This relation is also additive, people come to a “truth” for many different reasons – for example (in a scientific context) an initial experiment might not persuade a consensus, but a replication will persuade some more, and a prediction that bore out yet more, and so on.

Another insight is that truth is dynamic – authorities are not eternal, nor are consensuses. I’m just old enough to remember when Wikipedia was not a thing you could cite, but now (at least, according to school age children I interact with) you can use it when its articles cite sources. Psychology has provided lots of examples of overturned consensuses of late with the replication crisis, but it’s hardly unique to them – America’s Dad is rather less trusted than when I was a child, to put it mildly.

There is some resemblance to PageRank in these insights, though popularity and relevance aren’t quite what we’re after with “truth”. Regardless, I do think this definition gives a decent foundation for modeling how truth is actually determined in the real world.

In Which AI Does (Not) Save The Day

It’s 2025, so you can’t write a blog post in tech without an AI angle – I promise this one is actually relevant.

Also I’m a skeptic of the current AI push, as anyone checking my socials would know.

My experience with coding assistance is that they’re very good at producing variations of introductory material (which is already prevalent online) and very bad at the kinds of things I actually spend my time working on, which is always some niche issue. Maybe they can replace searching for tutorials or documentation, but I doubt they replace programmers. Perhaps Google should be worried – but I’m not. (As an aside, I consider this Apple paper good evidence that there’s no “intelligence” in these algorithms but that’s a topic for another post).

And yet…

LLMs are really interesting. They represent an advancement in natural language processing, even if all the “intelligence” stuff is wishful thinking. Topic modelling, translation, even some of the generative stuff – all massive improvements over prior work, and all runnable on commodity hardware.

How does this relate to truth? Well, if you had a model of truth (in keeping with my definition above) and wanted to classify a claim’s truth-ness in a consistent way (that is, citing your sources) could you do it with LLMs? I decided to find out.

The first stumbling block is that while I do believe my definition of truth is how people actually operate, there’s not a big TruthDB™ to query. But there’s something close (which I’ve sprinkled throughout this post, if you’ve been paying attention) – Wikipedia. Specifically, articles on Wikipedia which have inline citations to websites.

Why just those articles?

- Inline citations can be tied to specific claim in articles rather the whole article

- Citations can be verified by (a person) checking the link

So my sketched out pipeline was:

- Download Wikipedia

- Extract all relevant citations and articles

- Topic encode all articles

- For any claim I wanted to test:

- Topic encode the claim

- Take the top N (I used N = 5) most cosine-similar articles and their citations

- Use an entailment model to check if each statement with citation against the claim

- Spit out the results

For the topic modelling I used sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2, for the entailment model I used google/t5_xxl_true_nli_mixture, and for the glue I used some of the worst Javascript, C#, and Python you have ever seen. It was the holidays, I was in a rush 🤷♂️.

So does it work?

I came across this video with six false claims, a few of which were (IMO) testable, like…

In 2012, President Barack Hussein Obama repealed the Smith-Mundt act, which had been in place in 1948. The law prevented the government from putting its propaganda on TV and Radio.

So I ran it through and got… mixed results. The topic extraction does a decent job of finding relevant citations, but the entailment doesn’t meaningfully rank them and doesn’t identify the contradiction in a US President “repealing” a law – a power that office does not have.

As an example, the highest related sections extracted was this one:

The Act was developed to regulate broadcasting of programs for foreign audiences produced under the guidance by the State Department, and it prohibited domestic dissemination of materials produced by such programs as one of its provisions. The original version of the Act was amended by the Smith–Mundt Modernization Act of 2012 which allowed for materials produced by the State Department and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) to be made available within the United States.

Relevant citation was: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr4310/text

One other false claim from the same video.

Nazis are socialists.

Here the models did better, selecting many relevant sections and ranking these two as the most “counter” to it.

Nazism, formally National Socialism, is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany.

Citations: https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/189776/01b7ea57531a60126da86e2d5c5dbb78/parties_weimar_republic-data.pdf & https://www.britannica.com/event/Nazism

By the early 1920s, the party was renamed the National Socialist German Workers’ Party in order to appeal to left-wing workers, a renaming that Hitler initially objected to.

Citation: https://bibliotheques.paris.fr/Monteleson/doc/SYRACUSE/312027/naissance-du-parti-national-socialiste-allemand-les-debuts-du-national-socialisme-hitler-jusqu-en-19?_lg=fr-FR (note my crummy glue scripts failed to realize this was a book citation)

So, in this very limited test, the LLMs did kinda find relevant refutations / citations. I would never just trust the algorithm, you need a human in the loop (as with the Unfriendly Robot we built in a past life), but there’s some promise here.

The interesting thing here isn’t that these are good citations of refutations, but that the process is automated – automation scales, and gets cheaper per unit as it does. Plus I hacked this together in about a day and threw a laptop’s worth of compute at it for maybe a week – and most of that was in processing the Wikipedia dump files.

Can A Better Internet Be Built?

Today things kind of suck:

- We are awash in spam and scams

- LLMs are supercharging their generation

- Disinformation, willful and otherwise, is commonplace

- Our institutions are woefully failing to meet the challenges of the above

As I said earlier, I do think a lot of that is explained by the economics of disinformation. But maybe we already have the tools to change those?

It’d have to be something new – I don’t quite think anything that exists today is quite right.

- Wikipedia is too narrow and has too much baggage – though I imagine it’d be an important component of bootstrapping something new.

- Reddit is more focused on what is popular than what is true.

- Twitter is… well, a lot is wrong with Twitter. Community notes seem relevant although it’s too opaque about who is a part of the consensus.

- Bluesky (and Mastodon) are Twitter but not a nazi bar, which is commendable but not useful.

I don’t quite know what that new thing would be, but this little exercise did give me some small hope something could be built.

Another Optimization Exercise – Packing Sparse Headers

Posted: 2022/06/16 Filed under: code Comments Off on Another Optimization Exercise – Packing Sparse HeadersI recently came across an interesting problem at work, and found it was a good excuse to flex some newer .NET performance features (ref locals, spans, and intrinsics). So here’s part 2 of a series that started 6+ years ago.

The Problem

You’ve got a service that accepts HTTP requests, each request encoding many of its details in headers. These headers are well known (that is, there’s a fixed set of them we care about) but the different kinds of requests use different subsets of the headers, out of (say) 192 possible headers each kind of request uses (say) 10 or fewer of the headers. While headers come off the wire as strings, we almost immediately map them to an enumeration (HeaderNames).

Existing code interrogates headers in a few, hard to change, ways which defines the operations that any header storage type must support. Specifically, we must be able to:

- Get and set headers using the HeaderNames enumeration

- Get and set headers directly by name, i.e. someHeaderCollection.MyHeader = “foo” style

- Initialize from a Dictionary<HeaderNames, string>

- Enumerate which HeaderNames are set, i.e. the “Keys” case (akin to Dictionary<T, V>.Keys)

Originally this service used a Dictionary<HeaderNames, string> to store the requests’ headers, but profiling has revealed that reading the dictionary (using TryGetValue or similar) is using a significant amount of CPU.

A new proposal is to instead store the headers in a “Plain Old C# Object” (POCO) with an auto property per HeaderName, knowing the JIT will make this basically equivalent to raw field use (think something like this generated RequestHeaders class in ASP.NET Core). This POCO would have 192 properties making it concerningly large (about 1.5K per instance in a 64-bit process), which has caused some trepidation.

So the question is, can we do better than a Dictionary<HeaderNames, string> in terms of speed and better than the field-rich POCO in terms of allocation. We are going to assume we’re running on modern-ish x86 CPUs, using .NET 6+, and in a 64-bit process.

Other Approaches

Before diving into the “fun” approach, there are two other more traditional designs that are worth discussing.

The first uses a fixed size array as an indirection into a dynamically sized List<string?>. Whenever a header is present we store its value into a List<string?>, and the index of that string into the array at the index equivalent of the corresponding HeaderNames. This approach aims to optimize get and set performance, while deprioritizing the Keys case and only mildly optimizing storage. An implementation of this approach, called the “Arrays” implementation, is included in benchmarking.

The second still uses a Dictionary<HeaderNames, string> to store actual data, but keeps a 192-bit bitfield it uses to track misses. This approach optimizes the get performance when a header is repeatedly read but not present, at the cost of slightly more allocations than the basic Dictionary<HeaderNames, string> implementation. While interesting, the “repeatedly reading missing headers”-assumption wasn’t obviously true at work – so this is not included in benchmarking.

The “Fun” Approach

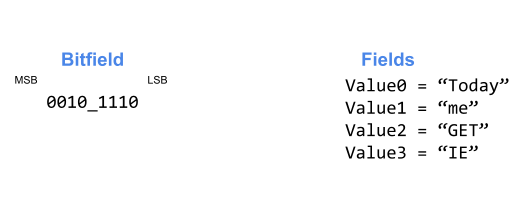

In essence, the idea is to pack the set headers and their values into an object with a 192-bit bitfield and 10 string fields. The key insight is that a bitfield encodes both whether a header is present and the index of the field it’s stored in. Specifically, the bit corresponding to a header is set when the header is present and the count of less significant bits is the field index its value is stored in.

To illustrate, here’s a small worked example where there are 8 possible headers of which at most 4 may be set.

Imagine we have the following enumeration:

enum HeaderNames { Host = 0, Date = 1, Auth = 2, Method = 3, Encoding = 4, Agent = 5, Cookie = 6, Cached = 7, }

Our state starts like so:

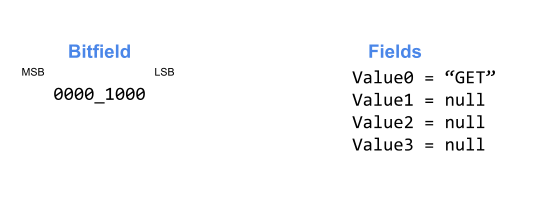

Setting Values

We set Method=”GET”, which corresponds to bit 3. There are no other bits set, so it goes in Value0.

Our state has become:

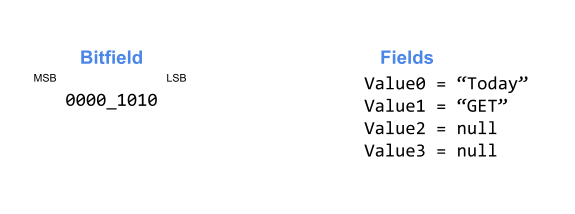

We then set Date=”Today”, which corresponds to bit 1. There are no less significant bits set, so we also want to store this value in Value0. We need to make sure there’s space, so we slide values 0-2 into values 1-3 before storing “Today” into Value0.

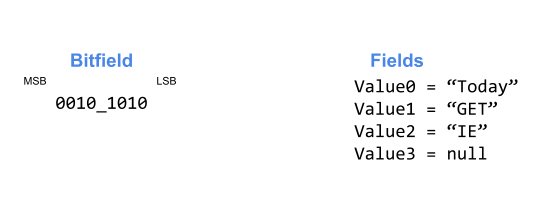

We now set Agent=”IE”, which corresponds to bit 5. There are 2 less significant bits set, so we want to store this into Value2.

Finally we set Auth=”me”, which corresponds to bit 2. There’s 1 less significant bit set, so we want to store this in Value1 after sliding values 1-2 into values 2-3.

We’re now full, so depending on our needs we can either start rejecting sets or push values that fall out of Value3 into some sort of “overflow” storage.

Getting Values

Looking up values is much simpler than setting them, we just check if the corresponding HeaderNames bit is set and if so count the number of less significant bits also set. That count is the index of the field storing the value for that header.

If we start from the state above:

- For Encoding we see that bit 4 in 0010_1110 is not set, so the Encoding header is not present

- For Method we see that bit 3 in 0010_1110 is set, so the Method header is set. The less significant bits are 0000_0110 which has 2 set bits and thus the value for Method is in Value2 – which is “GET”.

Implementation And Benchmarking

First, let’s implement all 4 approaches: the baseline Dictionary, the proposed Fields, Arrays, and Packed. While some effort has been made to be efficient (using value type enumerators, avoiding some branches, some [MethodImpl] hints, etc.) nothing too crazy has been done to any implementation.

In this blog post I’m only going to pull a few benchmark results out, but the full results are in the git repository. Note that all benchmarks have an iteration count associated with them, so times and allocations are comparable within a benchmark but not across benchmarks. Most benchmarks also explore a number of different parameters (like setting different numbers of headers, or varying the order in which they are set) – in this post I’m only pulling out basic results, but again the full results can be found in the repository.

Set By Enum (Code, Results)

Set benchmarks include allocation tracking, so they are a good place to start.

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Dictionary | 10, Random | 250.87 μs | 992.19 KB |

| Fields_V1 | 10, Random | 115.97 μs | 1523.44 KB |

| Arrays_V1 | 10, Random | 151.94 μs | 562.5 KB |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 329.09 μs | 117.19 KB |

Importantly, we see that we’ve accomplished our allocation goal – Packed and Arrays use much less memory than the Fields approach (92% and 63% less respectively), and even beat the Dictionary implementation (88% and 43% less respectively).

Unsurprisingly Fields is the fastest (being 64% faster than Dictionary), it’s very difficult to do better than accessing a field. Arrays isn’t that far behind (49% faster), while our first attempt with Packed is substantially slower (30% slower, in fact).

Set Directly By Name (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Dictionary | 10, Random | 273.27 μs | 992.19 KB |

| Fields_V1 | 10, Random | 120.12 μs | 1523.44 KB |

| Arrays_V1 | 10, Random | 199.65 μs | 562.5 KB |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 248.31 μs | 117.19 KB |

We do a little better with direct access, because we can hint to the runtime to inline the method behind our property Setters in Packed. This lets the JIT remove a bunch of operations since for any specific property the HeaderNames used is a constant, so a bunch of math gets moved to compile time.

This lets Packed start beating Dictionary by a modest 9%, while still being out speed by Arrays and Fields.

Get By Enum (Code, Results)

For these benchmarks, we read all 192 headers but vary the number of headers that are set.

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Dictionary | 10 | 152.79 ms |

| Fields_V1 | 10 | 198.32 ms |

| Arrays_V1 | 10 | 85.20 ms |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 99.86 ms |

It may seem odd that Fields is the slowest implementation here (being 30% slower than Dictionary), but that’s a consequence of using a switch to find the appropriate field. Even though our values are sequential so a switch becomes a simple jump table, that’s still a good amount of code and branching in each iteration.

Arrays is the fastest (about 44% faster than Dictionary), in part due to a trick where we store a null value in our values List<string?> so we don’t have to have a branch checking for 0s – that’s worth about 8% performance in a microbenchmark comparing the if and branchless version.

Packed doesn’t do badly, out performing Dictionary and Fields (faster by 35% and 50% respectively) and not too much slower than the Arrays approach (about 17%).

Get Directly By Name (Code, Results)

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Dictionary | 10 | 179.22 ms |

| Fields_V1 | 10 | 91.73 ms |

| Arrays_V1 | 10 | 95.96 ms |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 116.51 ms |

Here, as expected, Fields is a clear winner (49% faster than Dictionary). Arrays and Packed, while not as good as Fields, also outperform Dictionary (by 46% and 35% respectively).

Enumerator (Code, Results)

Each type has a custom enumerator (which implements IEnumerator<HeaderNames>, but is used directly) except for Dictionary which uses the built-in KeyCollection.Enumerator. Importantly, these enumerators do not yield values alongside the HeaderNames.

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Dictionary | 10 | 91.02 μs |

| Arrays_V1 | 10 | 123.53 μs |

| Fields_V1 | 10 | 2,003.25 μs |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 297.39 μs |

Finally, a benchmark that Dictionary wins – everything else is much slower, Fields is the worst at 21,000% slower, followed by Packed (220% slower) and Arrays (36% slower). The root reason for this is that, except for Dictionary, none of these implementations are really laid out for enumeration – Arrays has to scan a big (by definition mostly empty) array for non-zero values, Fields has to try reading all possible values (which in V1 involves that big switch mentioned in the Get By Enum benchmarks), and Packed has to do a lot of (in V1, rather expensive) bit manipulation.

Create With Dictionary (Code, Results)

Last but not least, initializing an instance of each type with a Dictionary<HeaderNames, string>. This is a separate benchmark because we can exploit the fact that we’re starting from an empty state to make certain optimizations, like skipping null checks.

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Dictionary | 10, Random | 96.02 μs | 453.13 KB |

| Fields_V1 | 10, Random | 125.20 μs | 1523.44 KB |

| Arrays_V1 | 10, Random | 164.36 μs | 562.5 KB |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 285.67 μs | 117.19 KB |

Another case where Dictionary is fastest, though by a much smaller margin. Following Dictionary, we have Fields, Arrays, and Packed which are 30%, 71%, and 198% respectively. I’d say this makes sense, Dictionary can simply copy it’s internal state in this case while all other implementations must do more work.

That’s it for the big benchmarks, so where are we starting from?

Overall, the Packed approach is much better in terms of allocations and decent in Get operations, beating Dictionary there but falling short of one or both of the Arrays and Fields approaches. It’s faster than Dictionary when Setting directly by name, but slower when Setting via an enum. And Packed is blown out of the water in Enumeration and Initialization.

If you had to choose right now, you’d probably go with the Arrays approach which has a strong showing throughout. Its only downside is that, while much smaller than the Fields proposal, it is larger than a Dictionary.

But of course, we can do better.

Replacing Switches With Unsafe.Add

Profiling reveals that a lot of time is being spent selecting the appropriate bitfield and values in Packed. This is simple code (just a small switch), so can we do better?

We can, by explicitly laying out the ulongs that hold our bitfield (and strings that hold our values) and turning the switch into a bit of pointer math. This technique is also applicable to the Fields approach, where a great deal of time is spent in simple switches. Using ref locals, ref returns, and Unsafe.Add we don’t need to actually use pointers (nor the unsafe keyword) but we are firmly in “you’d better know what you’re doing”-territory – reading or writing past the end of an instance is going to (eventually) explode spectacularly.

Microbenchmarking shows the “ref local and add”-approach is 4-5x faster than a three-case switch. New versions of Packed and Fields have these optimizations, and they are most impactful in…

Set By Enum (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Fields_V1 | 10, Random | 115.97 μs | 1523.44 KB |

| Fields_V2 | 10, Random | 95.25 μs | 1523.44 KB |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 329.09 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 320.21 μs | 117.19 KB |

Where Fields V2 is 18% faster than V1, and Packed V2 is 3% faster.

Get By Enum (Code, Results)

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Fields_V1 | 10 | 198.32 ms |

| Fields_V2 | 10 | 82.84 ms |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 99.86 ms |

| Packed_V2 | 10 | 90.40 ms |

Where Fields V2 is 59% faster than V1, and Packed V2 is 9% faster than V1.

Enumerator (Code, Results)

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Fields_V1 | 10 | 2,003.25 μs |

| Fields_V2 | 10 | 772.57 μs |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 297.39 μs |

| Packed_V2 | 10 | 293.06 μs |

Where Fields V2 is 61% faster, and Packed V2 is 1% faster.

Create With Dictionary (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Fields_V1 | 10, Random | 125.20 μs | 1523.44 KB |

| Fields_V2 | 10, Random | 115.61 μs | 1523.44 KB |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 285.67 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 278.97 μs | 117.19 KB |

Where Fields V2 is 8% faster, and Packed V2 is 3% faster.

Shifting Values With Span<string>

Another round of profiling reveals we should also try to optimize the switch responsible for moving values down to make space for new values in Packed. This is a trickier optimization, because the switch is doing different amounts of work depending on the value.

After some experimentation, I landed on a version that uses Unsafe.Add and Span<string> to copy many fields quickly when we need to move 4+ fields. Modern .NET is quite good at optimizing Span and friends but there is still a small opportunity I couldn’t exploit – we know the memory we’re copying is aligned, but the JIT still emits a (never taken) branch to handle the unaligned case.

This is about 50% faster in ideal circumstances, and matches the switch version in the worst case. Pulling this into our Packed approach (yielding V3) results in more gains compared to V2 in the various Set and Create benchmarks.

This code only runs when we’re setting values, so we see impacts in…

Set By Enum (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 329.09 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 320.21 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V3 | 10, Random | 175.95 μs | 117.19 KB |

Right away we see great improvement, Packed V3 is 45% faster than V2 when setting values by enum. This means our fancy Packed approach is now faster than using Dictionary (by 30%), though still shy of Arrays and Fields.

Set Directly By Name (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 248.31 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 249.11 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V3 | 10, Random | 204.55 μs | 117.19 KB |

Our gains are proportionally more modest when going directly by name, as we’re already pretty efficient, but we still see an 18% improvement in Packed V3 compared to V2. We’re now in spitting distance of Arrays (3% slower), though still way short of the Fields approach.

Create With Dictionary (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 285.67 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 278.97 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V3 | 10, Random | 200.12 μs | 117.19 KB |

Initializing from a dictionary falls between the two, where V3 sees a 29% improvement over V2.

Adding Intrinsics

Next step is to use bit manipulation intrinsics instead of longer form bit manipulation sequences. This is another tool that applies to multiple implementations – for the Arrays approach we can improve the enumerator logic scan for bytes using TZCNT, and with the Packed approach we can directly use POPCOUNT, BZHI, BEXTR, and TZCNT to improve all forms of getting and setting headers.

There’s also one, slightly irritating, trick I’m grouping under “intrinsics”. The JIT knows how to turn (someValue & (1 << someIndex)) != 0 into a BT instruction, while a multi-statement form won’t get the same treatment. This is a really marginal gain (on the order of 2% between versions) but I’d be in favor of BitTest (and BitTestAndSet) intrinsics in a future .NET so I could guarantee this behavior anyway.

Set By Enum (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 329.09 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 320.21 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V3 | 10, Random | 175.95 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V4 | 10, Random | 151.33 μs | 117.19 KB |

When setting by enum, V4 is worth another 24% speed improvement over V3. We’ve now more than doubled the performance of our original version.

Set Directly By Name (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 248.31 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 249.11 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V3 | 10, Random | 204.55 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V4 | 10, Random | 172.69 μs | 117.19 KB |

As with earlier improvements there’s less proportional win for this operation, but we still see a good 16% improvement in V4 vs V3.

Get By Enum (Code, Results)

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 99.86 ms |

| Packed_V2 | 10 | 90.40 ms |

| Packed_V3 | 10 | 80.81 ms |

| Packed_V4 | 10 | 75.98 ms |

Looking up by enumeration sees some small improvement, with V4 improving on V3 by 6%.

Get Directly By Name (Code, Results)

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 116.51 ms |

| Packed_V2 | 10 | 116.75 ms |

| Packed_V3 | 10 | 110.72 ms |

| Packed_V4 | 10 | 106.15 ms |

As does getting directly by name, with V4 being about 4% faster than V3.

Enumerator (Code, Results)

| Method | NumHeadersSetParam | Mean |

| Arrays_V1 | 10 | 123.53 μs |

| Arrays_V2 | 10 | 79.92 μs |

| Packed_V1 | 10 | 297.39 μs |

| Packed_V2 | 10 | 293.06 μs |

| Packed_V3 | 10 | 292.59 μs |

| Packed_V4 | 10 | 142.20 μs |

In part because neither approach is particularly well suited to the enumeration case, both Arrays and Packed see big gains from using intrinsics. Arrays V2 is 35% faster than V1, and Packed V4 is 51% faster than V3.

Create With Dictionary (Code, Results)

| Method | OrderAndCount | Mean | Allocated |

| Packed_V1 | 10, Random | 285.67 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V2 | 10, Random | 278.97 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V3 | 10, Random | 200.12 μs | 117.19 KB |

| Packed_V4 | 10, Random | 161.73 μs | 117.19 KB |

Finally, we see another 19% improvement in V4 vs V3.

Failed Improvements

There were a couple of things I tried that did not result in improved performance.

Combining Shifting And Field Calculation

Changing TryShiftValueDown to also return the field we need to store the value into. This yielded no improvement, probably because calculating the field is cheap and easily speculated.

Throw Helper

While never hit in any of the benchmarks, all implementations do some correctness checks (for things like maximum set headers, not double setting headers, and null values). A common pattern in .NET is to use a ThrowHelper to reduce code size (and encourage inlining) since calling a static method is usually more compact than creating and raising an exception (on the order of 10 instructions to 1).

This also didn’t yield any improvements, probably because these methods are so small already that adding a dozen or so (never executed) instructions didn’t push the code over any thresholds such that the impact of code size would become measurable.

Branchless Gets

It’s possible, through some type punning and adding an “always null” field to PackedData, to remove this if from Packed’s Get operations.

Basically, you calculate the notSet bool, pun it to a byte, subtract 1, sign extend to an int, and then AND with valueIndex + 1. This will give you a field offset of 0 if the HeaderNames’s bit is not set, and its valueIndex + 1 if it is. In conjunction with an always null field in PackedData at index 0 (causing all the value fields to shift down by one), you’ve now got a branchless Get.

This ends up performing much worse, because although we’re now branchless, we’re now also doing more work (including some relatively expensive intrinsics) on every Get. We’re also making our dependency chain a bit deeper in the “value is set”-case, which can also have a negative impact.

In fairness, this is an optimization that is likely to be heavily impacted by benchmark choices. Since my Get benchmarks tend to have lots of misses, this approach is particularly penalized. It is possible that a scenario where misses were very rare might actually benefit from this approach.

Maintain Separate Counts When Creating With Dictionary

My last failed attempt at an improvement was to try and optimize away the POPCOUNTs needed on adding each new header value when creating a Packed with a Dictionary.

The gist of the attempt was to exploit the fact that we’re always starting from empty in this case, and so we can maintain separate counts in the CreateFromDictionary method for each bitfield we’re modifying. Conceptually we needed three counts: one for the number of bits set before the 0th bitfield (this is always 0), one for the number of bits set before the 1st bitfield (this is the number of times we’ve set a bit in the 0th bitfield), and one for the number of bits set before the 2nd bitfield (this is the number of times we’ve set a bit in the 0th or 1st bitfields).

It’s possible to turn all that count management into a bit of pointer manipulating and an add, plus the reading of a value into more pointer manipulation and type punning. Unfortunately, this ends up being slower (though not by much) than the POPCOUNT approach. I suspect this is due to the deeper dependency chain, or possibly some cache coherence overhead.

Summing Up

After all these optimizations, we’ve managed to push this “Fun” Packed approach quite far. How does it measure up to our original goals, faster than Dictionary<HeaderNames, string>, while smaller than Fields?

We’ve been consistently smaller than a Dictionary and Fields, and managed to sustain that through all our optimizations. So that’s an easy win.

Considering Packed V4’s performance for each operation in turn:

- Set By Enum – 40% faster than Dictionary, but 59% slower than Fields

- Set Directly By Name – 37% faster than Dictionary, but 48% slower than Fields

- Get By Enum – 50% faster than Dictionary, and 8% faster than Fields

- Get Directly By Name – 41% faster than Dictionary, but 16% slower than Fields

- Enumerator – 56% slower than Dictionary, but 82% faster than Fields

- Create With Dictionary – 68% slower than Dictionary, and 40% slower than Fields

It’s a bit of a mixed bag, though there’s only one operation (Initializing From Dictionary) where Packed has worse performance than both Dictionary and Fields. There’s also one operation (Get By Enum) where Packed out performs both.

I’d be comfortable saying Packed is a viable alternative, given the operations it underperforms Dictionary in are the rarer ones and Fields is only actually better at one of those.

It’s worth noting that the Arrays approach is also pretty viable, though its space savings are much more modest (being 380% bigger than Packed, but still 37% the size of Fields in the fully populated cases). Arrays is out performed by Packed in the Set Directly By Name, Get By Enum, and CreateWith Dictionary operations but is better or comparable in the rest.

So yeah, this was a fun exercise that really let me try out some of the newer performance additions to .NET.

Miscellanea

Some clarifications and other things to keep in mind, that didn’t fit neatly anywhere else in this post.

- Benchmarking is always somewhat subjective and while I’ve attempted to mimic the actual use cases we have, it is probably possible to craft similar benchmarks that produce quite different results.

- All benchmarks were run on the same machine (a Surface Laptop 4, plugged in, on a high performance power plan) that was otherwise idle. Relevant specs are included in each benchmark result file.

- Some operations are influenced by the data values, not just the data count. For example, Set operations may spend more time shifting values if the certain HeaderNames are set before others. Where relevant, full benchmarks explore best and worst case orderings. In this post, random order is what was cited as the most “realistic” option but in certain use cases other orderings may be more appropriate.

- This implementation assumes 192 header values, while the motivating case actually has somewhere between 150-160. Since the number of headers in that case is expected to grow over time, and there’s no inherently “correct” choice, I chose to benchmark “the limit” for the Packed approach. This favors Packed somewhat in terms of allocations, and penalizes the V1 of Fields in terms of speed. These biases do not appear to be enough to change any of the conclusions.

- 10 set headers comes from the motivating case, but it also results in Packed being 120 bytes in size (16 bytes for the object header, 8 bytes each for the three bitfields, and 8 bytes each for the ten string references). This fits nicely in one or two cache lines for most CPUs (compared to Fields’ 25 or 13 cache lines), while also leaving space to stash a reference to store “overflow” headers if that’s desired.

- There are non-intrinsic versions of TZCNT and POPCOUNT, which fall back to slower implementations when the processor you’re executing on doesn’t support an intrinsic. I avoided using these because, in this case, the performance is the point – I’d rather raise an exception if the assumption that the operation is fast is false.

Overthinking CSV With Cesil: .NET 5

Posted: 2021/05/26 Filed under: code | Tags: cesil Comments Off on Overthinking CSV With Cesil: .NET 5The latest release of Cesil, 0.9.0, now targets .NET 5. Along with some free performance, .NET 5 and C# 9 bring some new features which Cesil now either uses or supports.

Free Performance

It’s no secret that each new .NET Core release has come with some performance improvements, and even though .NET 5 has dropped “Core” it hasn’t dropped that trend. My own benchmarking suggests about 10%, in libraries like Cesil.

Of course, there are more performance improvements available if you’re willing to make code changes. The biggest once for Cesil was…

The Pinned Object Heap

The Pinned Object Heap (POH) is a new GC heap introduced in .NET 5, and as the name suggests it’s distinguishing feature is that everything allocated in it is pinned. For those unfamiliar, in .NET an allocation can be pinned (via a fixed statement, a GCHandle, etc.) which prevents the garbage collector from moving it during a GC pass.

As you’d expect, pinning an allocation complicates GC and can have serious performance implications which means the historical advice has been to avoid holding pins for long periods of time. For code, like Cesil, which is heavily asynchronous this is extra difficult as “a long time” can happen at any await expression. Of course, pinning isn’t free so you don’t want to unpin memory that you’re going to immediately repin either.

Before 0.9.0, Cesil had quite a lot of code in it that managed pinning and unpinning the bits of memory used to implement parsing CSV files. By using the POH, I was able to remove all this code – keeping the performance benefits of some pointer-heavy code without gumming up the GC. Naturally, since the fastest code is the code that never runs, removing this code also improved Cesil’s overall performance.

A word of caution, almost all allocations should remain off the POH. Cesil allocates very little on the POH, one constant chunk for state machine transition rules, and a small amount of memory for each IBoundConfiguration (instance of which should be reused). Accordingly, during normal read & write operations Cesil won’t allocate anything new on the POH.

Naturally, performance isn’t the only improvement in .NET 5 there are also new features like…

Native (Unsigned) Integers

Native integers have always existed in .NET, but C# 9 exposes them more conveniently as nint and nuint. These are basically aliases for IntPtr and UIntPtr, but those were somewhat awkward to use in earlier C# versions.

Cesil now supports reading and writing nint and nuint, including when using Cesil.SourceGenerator. Extra care must be taken when using them, as their legal range depends on the bittage of the reading and writing processes.

Init-Only Setters

C# has supported get-only properties and private setters for a while, however it was not possible to idiomatically express “properties which may only be set at initialization time”. C# 9 adds init; as a new syntax to allow this, a great addition in my opinion.

At runtime, init-only setters required no changes in Cesil. They do greatly complicate source generators, however, as it is now necessary to set all init-only properties at the same time. This is similar to constructor parameters except that constructor parameters are always required to be present, but properties are inherently optional.

Record Types

The biggest new addition to C#, record types are a terser way to declare classes that primarily encapsulate data. They’re a simple idea that actually has a lot of complication behind the scenes, primarily around how they interact with inheritance.

To be blunt, while Cesil does support record types I’d discourage doing anything with them beyond the simplest declarations. Basically anything with inheritance, non-primary constructors, or additional properties is asking for trouble. Cesil does what it can to choose reasonable defaults, but behavior can be surprising.

For example, given this declaration:

record A(int Foo);

record B(string Bar) : A(Bar.Length);Deserializing a string like “Foo,Bar\r\n123,hello” to an instance of B will initialize Foo twice, leaving it equal to 123. Meanwhile deserializing “Bar\r\nhello” will initialize Foo once to 5. If you de-sugar what records are actually doing this “makes sense” as Foo is set in A’s constructor and then again when B is initialized (which is legal, as Foo is init-only), but I’d argue it’s unintuitive.

[DoesNotReturn] And Coverage

Pretty minor for most, but really big for Cesil, is that .NET now ships with a DoesNotReturnAttribute. Along with some changes to Coverlet, this allowed a lot of code that was in place to reduce noise in coverage statistics to be removed.

And that’s about it for .NET 5 and Cesil. .NET 6 is already in preview, promising some more performance improvements and exciting new types to support, so I’ve even more improvements for Cesil to look forward to.

I’m nearing the end of the planned posts in this series – next time I’ll go over any standing open questions and their resolutions, as I prepare for the Cesil 1.0 release.

Overthinking CSV With Cesil: Source Generators

Posted: 2021/02/05 Filed under: code | Tags: cesil Comments Off on Overthinking CSV With Cesil: Source GeneratorsAs of 0.8.0, Cesil now has accompanying Source Generators (available as Cesil.SourceGenerators on Nuget). These allow for Ahead-Of-Time (AOT) generation of serializers and deserializers, allowing Cesil to be used without runtime code generation.

What the heck is a Source Generator?

Released as part of .NET 5 and C# 9, Source Generators are a really cool addition to the C# (and VB.NET) compiler (also known as Roslyn). They let you hook into the compiler and add additional source code to a compilation, and join Analyzers (which let you raise custom warnings and errors as part of compilation) as official ways to extend the .NET compilation process.

Source Generators may sound like a small addition – after all, generating code at compile time has a long history even in .NET with things like T4, and (some configurations of) Razor. What sets Source Generators apart is their integration into Roslyn – so you get the actual ASTs and “semantic models” the compiler is using, you’re not stuck with string manipulation or home grown parsers.

Having the compiler’s view of the code makes everything more reliable, even relatively simple things like finding all the uses of an attribute. In the past where I would have done a half-baked approach looking for various string literals (and ignoring aliases and other “hard” problems, now you just write:

// comp is a Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.Compilation

var myAttr = comp.GetTypeByMetadataName("MyNamespace.MyAttribute");

var typesWithAttribute =

comp.SyntaxTrees

.SelectMany(

tree =>

{

var semanticModel = comp.GetSemanticModel(tree);

var typeDecls = tree.GetRoot().DescendantNodesAndSelf().OfType();

var withAttr =

typeDecls.Where(

type =>

type.AttributeLists.Any(

attrList =>

attrList.Attributes.Any(

attr =>

{

var attrTypeInfo = semanticModel.GetTypeInfo(attr);

return myAttr.Equals(attrTypeInfo.Type, SymbolEqualityComparer.Default);

}

)

)

);

return withAttr;

}

);

If you prefer LINQ syntax, you can express this more tersely.

var myAttr = comp.GetTypeByMetadataName("MyNamespace.MyAttribute");

var typesWithAttribute = (

from tree in comp.SyntaxTrees

let semanticModel = comp.GetSemanticModel(tree)

let typeDecls = tree.GetRoot().DescendantNodesAndSelf().OfType()

from type in typeDecls

from attrList in type.AttributeLists

from attr in attrList.Attributes

where myAttr.Equals(semanticModel.GetTypeInfo(attr).Type, SymbolEqualityComparer.Default)

select type

).Distinct();

It’s also really easy to test Source Generators. There’s a bit of preamble to configure Roslyn enough to compile something, but it’s all just Nuget packages in the end – and once you’ve got a Compilation it’s a simple matter to use a CSharpGeneratorDriver to run an ISourceGenerator and get the updated Compilation. With that done, extracting the generated source or emitting and loading an assembly is a simple matter. For Cesil I wrapped all of this logic up into a few helper methods.

How to use Cesil’s Source Generators

First, you need to add a reference to the Cesil.SourceGenerator nuget project. The versions of Cesil and Cesil.SourceGenerator must match, for reasons I discuss below.

After that, the simplest cases (all public properties on POCOs) just require adding a [GenerateSerializer] or [GenerateDeserializer] to a class, and using the AheadOfTimeTypeDescriber with your Options. For cases where you want to customize behavior (exposing fields, non-public members, using non-property methods for getters and setters, custom parsers, etc.) you apply a [DeserializerMember] or [SerializerMember] attributes with the appropriate options.

For example, a class that uses a custom Parser for a particular (non-public) field would be marked up like so:

namespace MyNamespace

{

[GenerateDeserializer]

public class MyType

{

[DeserializerMember(ParserType = typeof(MyType), ParserMethodName = nameof(ForDateTime))]

internal DateTime Fizz;

public static bool ForDateTime(ReadOnlySpan data, in ReadContext ctx, out DateTime val)

=> DateTime.TryParse(data, out val);

}

}

There are a few extra constraints when compared to the runtime code generation options Cesil gives you. Since we’re actually generating source, anything exposed has to be accessible inside to that generated code – this means private members and types cannot be read or written. At runtime, Cesil lets you use delegate for most customization options (like Parsers, Getters, and so on) – this isn’t an option with Source Generators because delegates cannot be passed to attributes (nor do they really “exist” at compile time, in the same way they do at runtime).

How Cesil’s Source Generators work

While Source Generators are pretty new, it seems like things are settling on a few different forms:

- Filling out partials

- For these, a partial type (potentially with partial members) is filled out with a source generator.

- This means the types being “generated” (and uses of its various members) already exist in the original project, however the partial keyword lets the actual code in tha type be generated.

- An example is StringLiteralGenerator.

- Generating new types based on attributes, interfaces, or base classes

- For these, a whole new type is generated based on an existing type in the original project.

- This means the types being generated don’t appear in the original project, and are presumably found via reflection (but not code generation) at runtime.

- An example is Generator.Equals.

- Generating new types based on non-code resources

- For these, generated code is generated from something other than C# code. While this must be found somehow through some configuration in the project, the logical source could be a database, the file system, an API, or really anything.

- As with #2, this implies the generated types are found dynamically at runtime.

- An example is (or will be) protobuf-net.

Cesil is an example of #2, each annotated type gets a (de)serializer class generated at compile time and the AheadOfTimeTypeDescriber knows how to find these generated classes given the original type. A consequence of this design is that some runtime reflection does happen, even though no code generation does.

There’s something of a parallel consideration for Source Generators as well: whether the source generated is something that could have been handwritten in a supported way, versus generated code that is an implementation detail. I think of this distinction as being the difference between automating the use of a “construction kit”-style library (say protobuf-net’s protogen, which generates C# that uses only the public bits of protobuf-net), and those that merely seek to avoid runtime code generation but may rely on implementation details to do so.

Cesil’s Source Generators are of the latter style, the code they generate uses conventions that are not public and may change from version to version. This is the main reason that you can only use the Cesil.SourceGenerator package with a Cesil package of the exact same version, as I mentioned above. Another reason is the versioning rough edge discussed below.

Viewing one of the generated classes can illustrate what I mean:

//***************************************************************************//

// This file was automatically generated and should not be modified by hand.

//

// Library: Cesil.SourceGenerator

//

// Purpose: Deserialize

//

// For: MyNamespace.MyClass

// On: 2021-01-26 20:34:50Z

//***************************************************************************//

#nullable disable warnings

#nullable enable annotations

namespace Cesil.SourceGenerator.Generated

{

#pragma warning disable CS0618 // only Obsolete to prevent direct use

[Cesil.GeneratedSourceVersionAttribute("0.8.0", typeof(MyNamespace.MyClass), Cesil.GeneratedSourceVersionAttribute.GeneratedTypeKind.Deserializer)]

#pragma warning restore CS0618

internal sealed class __Cesil_Generated_Deserializer_MyNamespace_MyClass

{

// ... actual code here

}

}

(As an aside, a handy tip for developing Source Generators: setting EmitCompilerGeneratedFiles to true and CompilerGeneratedFilesOutputPath to a directory in your .csproj will write generated C# out to disk during compilation)

Rough edges with Source Generators

Of course, not everything is perfect with Source Generators. While very, very cool in my opinion there are still some pretty rough edges that you’ll want to be aware of.

- Roslyn and Visual Studio versioning are still painful

- Since introduction, using the “wrong” version of Roslyn in an Analyzer has broken Visual Studio integration. This makes some sense (any given Visual Studio version is using a specific Roslyn version internally, after all) but is just incredibly painful during development, especially if you’re routinely updating dependencies and tooling.

- Source Generators have exactly the same problem, except now such breaks affect things more important than your typical diagnostic message.

- At time of writing (and for Visual Studio 16.8.4) you must package a SourceGenerator which targets netstandard2.0, and references Roslyn 3.8.0. Any other combination might work in tests, but cannot be made to work reliably with Visual Studio.

- Over time I expect this to get pretty painful if you try to support older Visual Studio (and implicit, Roslyn) versions with your latest package versions.

- These concerns are part of why I split Cesil’s Source Generators into a separate package, so I can at least keep that pain away from the main Cesil code.

- Source Generators are testable, but you’ll be rolling your own conventions

- Any Source Generator is likely to be broken up into separate logical steps – in Cesil these are: finding needed types, discovering annotated types, mapping members on those types to columns, generating any parsers or formatters needed, and generating the actual (de)serializer type.

- However, ISourceGenerator just gives you two methods – and you’ll probably only use Execute(). “Partially” running a Source Generator isn’t a thing, and the passed contexts are not readily mock-able. So you’ll have to break things up and test them however makes sense to you, there’s nothing really built-in to guide you.

- For Cesil, I exposed the results of these interim steps as internal properties and used those in tests. It would be just as valid to break those steps into separate classes, or wrap contexts in your own types to enable mocking, or anything really.

- Some things you’d expect to be one-liners aren’t

- With generated code, especially using other code as inputs, there’s lots of small tasks you’d expect to have to do. Some of these are simple tasks with Roslyn, like NormalizeWhitespace(), but lots aren’t. Examples include:

- Removing unused usings from a file

- Inlining a method call

- Converting a generic type or method to a concrete one, via substituting a type

- Telling if a type needs to be referred to in a particular manner (ie. fully qualified or not) in a given block of code

- All of these things are doable with Roslyn, and oftentimes there’s example code out there, but none of them are trivial. Inlining in particular is something I’d expect lots of folks to need, but isn’t built-in and requires a lot of care to get right (with Cesil I settled on only inlining some very specific calls, in order to avoid the complexity of the more general case).

- In theory these sorts of things could be provided via a third-party library, but shipping dependencies with Source Generators (and Analyzers) is painful because of the versioning issues in #1 – so they kind of need to be built-in in my opinion.

- With generated code, especially using other code as inputs, there’s lots of small tasks you’d expect to have to do. Some of these are simple tasks with Roslyn, like NormalizeWhitespace(), but lots aren’t. Examples include:

- A big use case for Source Generators is avoiding runtime code generation. However, there’s no easy way to check that you have avoided runtime code generation.

- There are some runtimes (like Xamarin.iOS) that don’t allow runtime code generation, full stop. Building and running tests on these would be a kind of check, but that’s far from easy.

- It’d be nice if there was a way to “electrify” the runtime to cause runtime code generation to fail. A less attractive, but easier, option would be to document what types or methods depend on runtime code generation – then an Analyzer could be written that flags uses.

And that about covers Source Generators, and Cesil’s use of them. While I have no specific Open Questions for this topic, any feedback on these Source Generators is welcome – just open an Issue over on GitHub. Next time, I’m going to go over the other new features in C# 9 and .NET 5 and talk about how Cesil is using them.

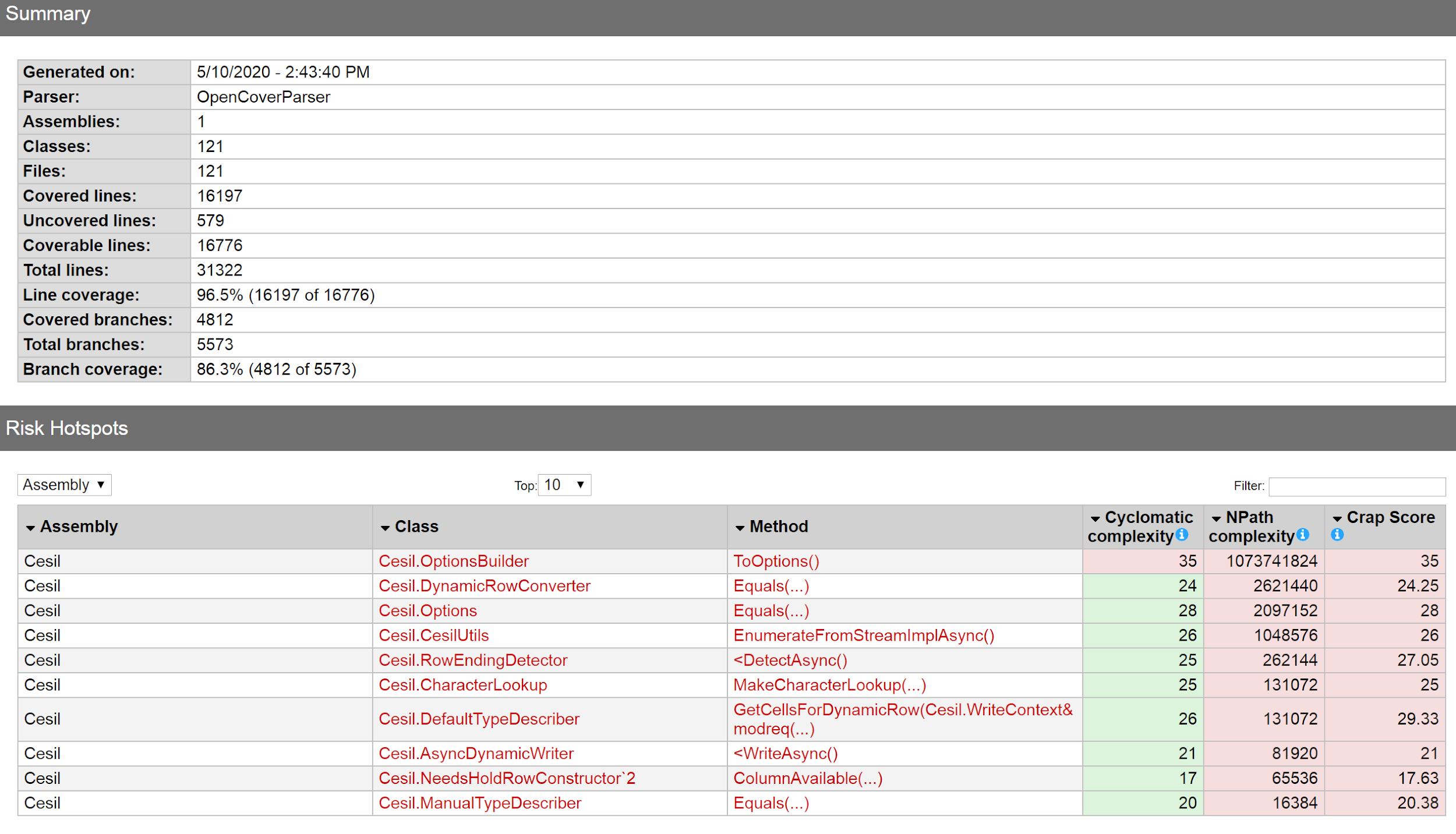

Overthinking CSV With Cesil: Performance

Posted: 2020/11/20 Filed under: code | Tags: cesil Comments Off on Overthinking CSV With Cesil: PerformanceIt’s time to talk about Cesil’s performance.

Now, as I laid out in an earlier post, Cesil’s raison d’etre is to be a “modern” take on a .NET CSV library – not to be the fastest library possible. That said, an awful lot of .NET and C#’s recent additions have had an explicit performance focus. Just off the top of my head, the following additions have all been made to improve performance:

- RyuJit

- Span<T> (and friends)

- Pipelines

- ref structs

- safe stackalloc

- ValueTask

- unmanaged constraint

- ValueTuple

- Intrinsics

- An awful lot of .NET Core

Accordingly, I’d certainly expect a “modern” .NET CSV library to be quite fast.

However, I deliberately chose to wait until now to talk about Cesil’s performance. Since I was actively soliciting feedback on capabilities and interface with Cesil’s Open Questions, it was a real possibility that Cesil’s performance would change in response to feedback. Accordingly, it felt dishonest to lead with performance numbers that I knew could be rapidly outdated.

The Cesil solution has a benchmarking project, using the excellent BenchmarkDotNet library, which includes benchmarks for:

- Reading and Writing static types

- These include comparisons to other CSV libraries

- Reading and Writing dynamic types

- These are compared to their static equivalents

- Various internals

- These are compared to naïve alternative implementations

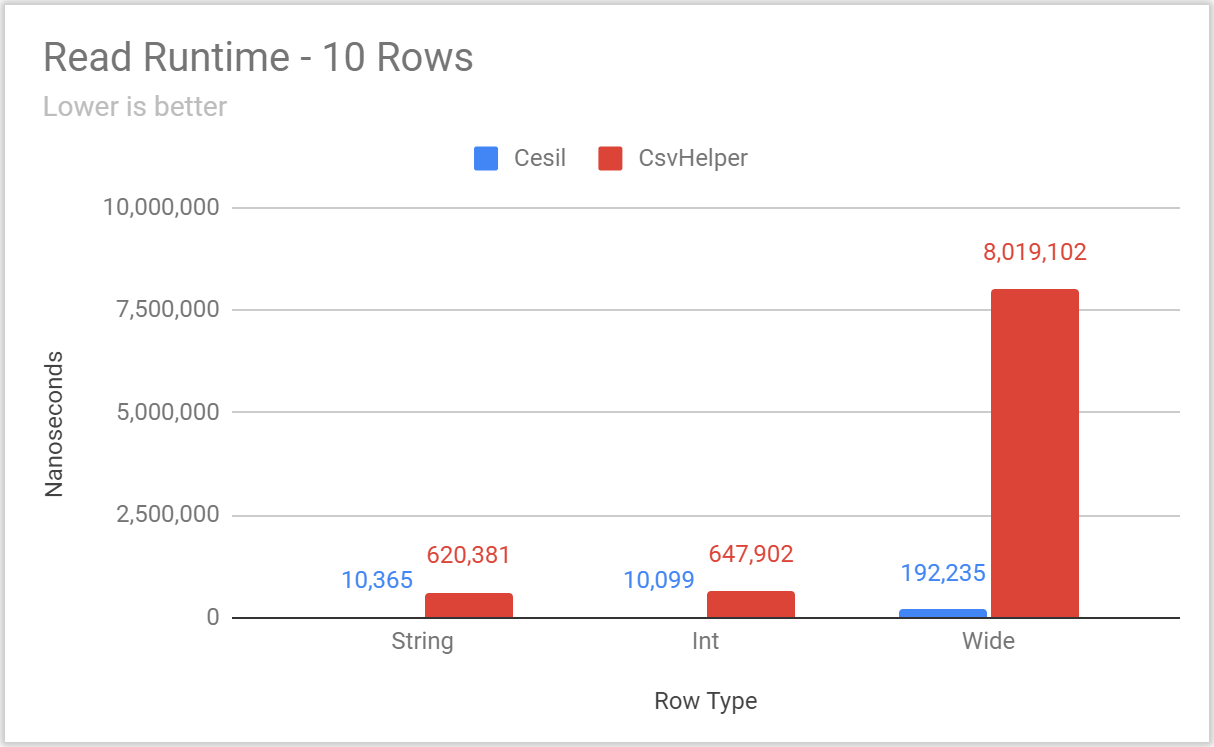

The command line interface allows selecting single or collections of benchmarks, and running them over ranges of commits – which enables easy comparisons of Cesil’s performance as changes are made.